Introductory note: One of the most interesting developments in 2020 was an incredible surge in SPAC activity, which became one of the largest IPO segments. In this guest post, Reed Sherman, lead analyst at Wolfpack Research, addresses and analyzes the private equity industry's possible angles on this SPAC boom. Breakout Point thanks Reed and Wolfpack for this truly insightful guest post. Credit for all of the private equity data used in the charts goes to PitchBook. Disclaimer: The following guest post does not necessarily reflect the views of Breakout Point, our full disclaimer is available here.

Why Private Equity Has Jumped on the SPAC Boom of 2020

Guest post by Reed Sherman – Wolfpack Research

Introduction

Prior to joining Wolfpack in early 2019, I spent just over 6 months working as an Analyst for a Private Equity ("PE") fund in Austin, Texas. During that time, I noticed that the PE industry was quietly dealing with a significant problem: EV/EBITDA multiples had peaked in 2014, and many funds were struggling to find exits for their aging portfolio companies that would produce returns anywhere near their target IRRs. In short, they were running out of time to find buyers for investments they overpaid for years earlier.

PE investments are inherently less liquid than publicly traded securities. To compensate for this, General Partners (“GPs”) provide their Limited Partners (“LPs”) with very specific timelines and high expected rates of return to encourage investment in their funds. The timeline is generally around 5 years from investment to exit and the target IRR (the annualized return effectively promised to LPs) is usually between 20% and 30%.

PE funds could generally achieve these outsized returns over a five-year period for two key reasons. The first is that PE funds had (historically) added significant value to their portfolio companies during that five-year period. They would come in with a specific “playbook” to grow the company at the necessary clip to generate their target IRR without relying on selling the company at a higher EV/EBITDA multiple than they paid. The second is slightly less obvious, but still simple. Leverage: the more debt used in the initial deal, the higher the exit IRR, all else equal. So, achieving the target IRR during the promised timeline shouldn’t be a problem, right?

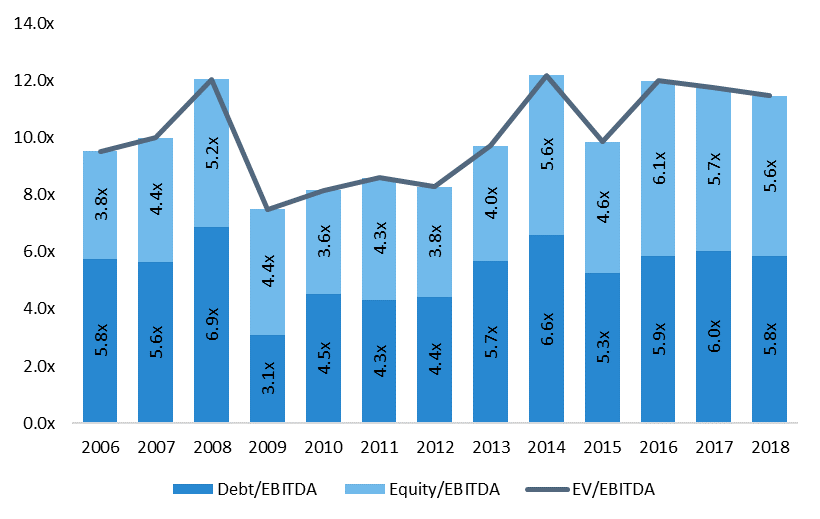

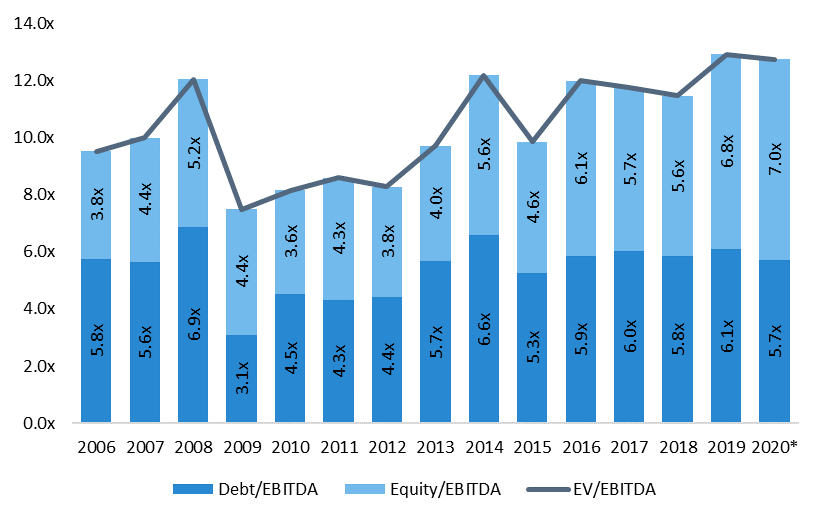

Unfortunately, it’s not quite that easy. Multiple contraction creates big problems for PE funds and, as shown in the figure below, in 2018 buyout multiples had contracted since their post-GFC peak in 2014:

Why was the 2014 peak so important in 2018? Well, PE funds that paid the 12.2x average EV/EBITDA multiple in 2014 were looking for exits, as they had promised their LPs liquidity five years after their initial investment. IPOs had already become a much less common exit for PE portfolio companies, only 4% of PE exits in 2018 were via IPOs.

While strategic buyouts by large corporations had long been the favorite exit option for PE firms – Vista Equity Partners’ $4.75 billion sale of Marketo to Adobe comes to mind – but with interest rates rising (remember, this was 2018 when Jerome Powell was in the process of raising the Fed Funds rate to the unsustainable high of 2.25%) and volatility returning to markets after a historically calm year in 2017, who was going to pay a premium multiple to provide the returns investors were expecting in 2019?

As it turns out, aging PE funds were already resorting to Secondary Buyouts for many of their exits.

The Rise of Secondary Buyouts

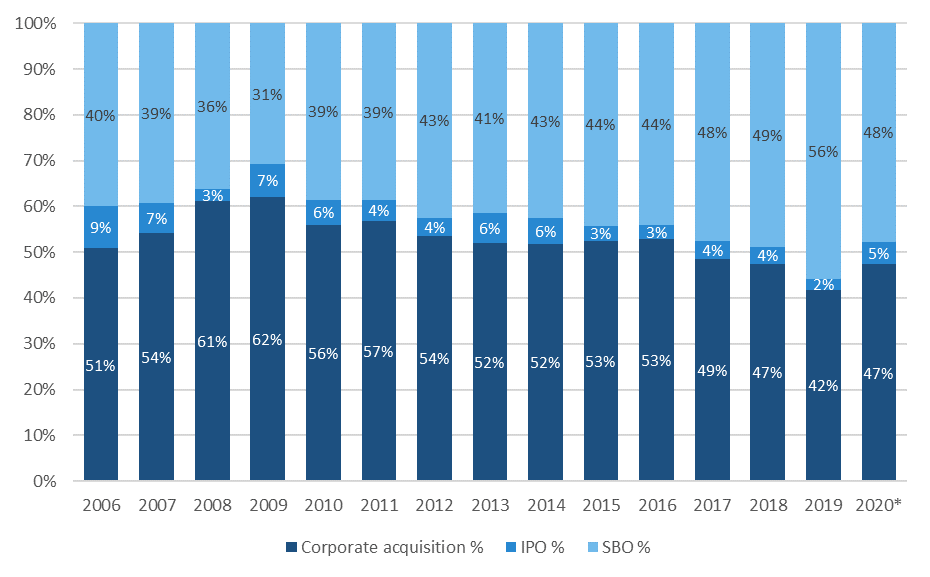

While they were common over the prior decade, 2018 was the first year in history where Secondary Buyouts (“SBOs”) had accounted for the majority of PE exits, as shown in the figure below:

For those unfamiliar, an SBO is just an Leveraged Buyout (“LBO”) where the buyer and seller are both private equity funds. SBOs merely create the illusion of an exit by shifting the portfolio company from one PE fund to another, often within the same firm. Funds managed by the same firm tend to have many of the same LPs, so it is not uncommon for an LP to be an investor in both the exiting fund and the acquiring fund involved in an SBO – effectively buying the company from themselves while the brokers, bankers and GPs all collect fees on the transaction.

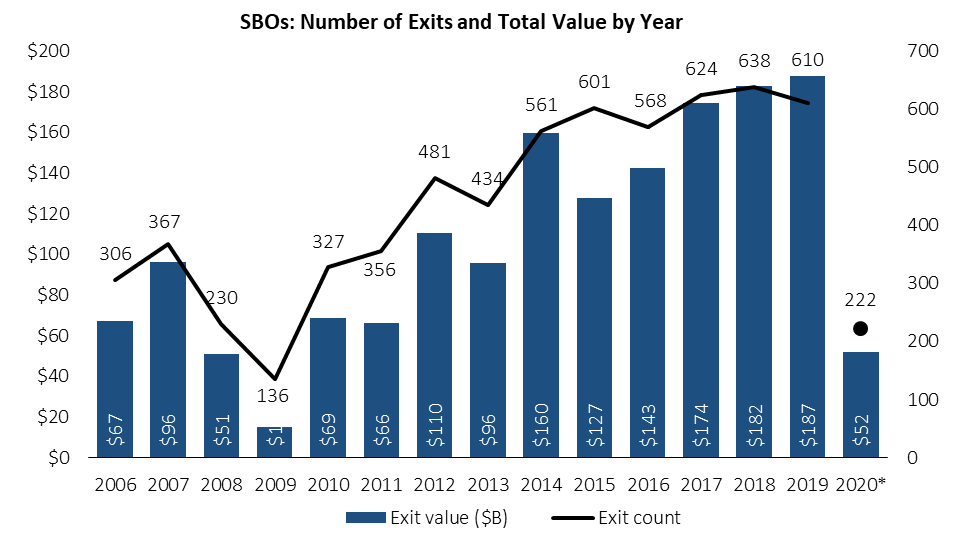

Imagine, if you will, buying a house from yourself: you pay commission to the realtor and all the taxes and fees associated with the sale, but at the end of the day you’re left with the same house you had before. Is this worth it for the LPs? Obviously not. A study conducted by Harvard Business School quantified the downside of SBOs – they found that, on average, LPs earned a 15% lower IRR on SBOs than on LBOs. GPs massaged this problem by using more leverage in each subsequent buyout, providing their LPs with some liquidity, as the increased leverage allowed GPs to return some equity to their LPs. This trend ballooned in 2019 when Jerome Powell abandoned his attempt to normalize interest rates. The ensuing rate cuts led to SBOs accounting for a remarkable 56% of PE exits in 2019; 610 deals for a total of $187 billion in 2019, as shown in the figures below:

Clearly this cycle of SBOs could not go on indefinitely. Secondary Buyouts turned into Tertiary Buyouts, which then turned into Quaternary Buyouts, and so on. The question of “how much value could a third or forth PE fund possibly add to a company?” became impossible to ignore. Furthermore, even PE funds can only take on so much leverage before the risk management department at the firm, or lenders themselves, stopped allowing funds to take on additional leverage for these deals.

At the end of the day, the PE funds had sucked everything they could out of these companies and needed to find another exit strategy. They did, of course, in a semi-esoteric vehicle that many people had never heard of prior to 2020: Special Purpose Acquisition Companies, better known as SPACs.

The SPAC Boom of 2020: Private Equity’s New Exit Strategy

The SPAC boom of 2020 emerged just in time for PE funds looking for exits. SBOs were becoming a less viable option as other PE funds deleveraged amid the financial and economic shock that was particularly acute at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Of course, the timing of the rise of SPACs was not entirely coincidental. Many Private Equity firms began sponsoring SPACs, fueling the boom from both sides. From a PE fund’s point of view, sponsoring a SPAC not only provided highly favorable economics but created a massive pool of new de-facto LPs (i.e., retail investors) who were willing to invest in a portfolio that would be concentrated in a single stock.

From the exiting PE funds’ point of view, SPACs were the perfect solution to their SBO problem. By selling to a SPAC, the GP could retain equity upside that was liquid and could be sold for a significant profit shortly after the SPAC merger was consummated, as SPACs have much looser lockup requirements than traditional IPOs. At the same time, SPAC exits provided liquidity to the LPs at IRRs in excess of the fund’s target IRR and could be completed in much less time than a traditional IPO.

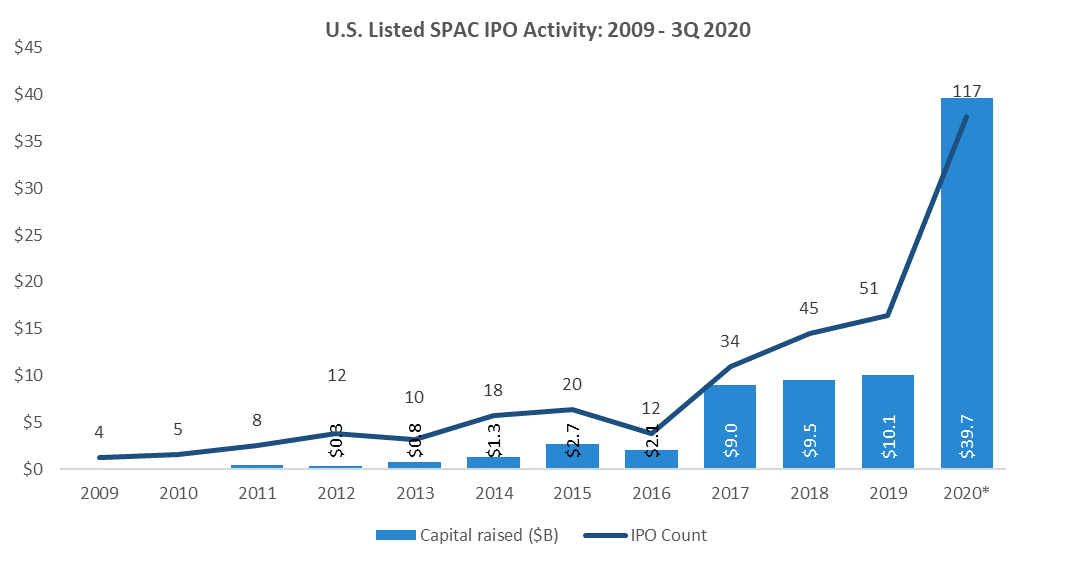

Due to all the advantages SPACs provide to PE funds, I was not surprised in the least when I saw the massive increase in SPAC IPO activity during the first 3 quarters of 2020. During that period alone, SPAC IPOs raised $39.7 billion – more than the total amount of money raised by SPACs between 2009 and 2019 combined. The number of SPAC IPOs more than doubled in the first three quarters of 2020 compared to 2019, as shown in the figure below:

Investors Beware

I need to preface this section with a disclaimer: I am not a Registered Financial Advisor, nor do I hold any licenses with the SEC, FINRA or any other regulatory agency. This is not investment advice and should not be construed as such.

Having said that, I would strongly encourage investors to do as much research as possible before investing in a SPAC. I would be especially weary of SPACs sponsored by PE firms, and even more skeptical of companies that SPACs acquire from PE funds.

More specifically, I would research the company’s history with private equity. How many buyouts have they already been through? Personally, I would not invest in a SPAC that is acquiring a company from PE at all – especially if the company has been through more than one buyout in the PE market. As I mentioned earlier, how much growth potential can there possibly be in an aging company that has had its value “maximized” by two, three or even four-plus different PE funds? In my opinion, the answer is little-to-none.

A great example was written about by Muddy Waters Research (“MW”) earlier this year: MultiPlan Corporation (NYSE: MPLN). You can find MW’s report on MPLN here. MW makes many compelling points in this report that confirmed my suspicions of PE’s questionable intentions taking advantage of the SPAC boom.

First, MW points out that the SPAC, Churchill Capital Corp. III, purchased MultiPlan from its fourth consecutive private equity group. Further, MW points out that while Churchill touted that the seller, PE firm Hellman & Friedman (“H&F”) would retain a significant equity stake, this appears to be a misleading point. MW believes that the SPAC seemed to be H&F’s last possible option to unload MPLN. Even worse, H&F had allegedly already taken a significant portion of its investment off the table through dividends MPLN paid to H&F prior to the SPAC deal, which substantially increased MPLN’s net leverage.

I strongly suggest all readers of this article read MW’s full report on MPLN, as Carson does a fantastic job explaining the financial engineering H&F seemingly used to make MPLN’s financials appear much more favorable than they were at the time of the acquisition.

I believe there will be many more SPAC deals over the next year or two that involve seemingly similarly egregious financial engineering to help PE funds exit their aging, deteriorating investments made at premium multiples after years of being passed from PE fund to PE fund.

Again, this is only my opinion and should not be taken as investment advice. Not all SPACs are bad, but not all SPACs are good, either. Do your own research, and be weary of financial engineering done by Private Equity sellers – if there is one thing I can say definitively about PE people it is this: they are incredibly smart and know how to make financial statements look better than they actually are.

Many thanks to Breakout Point for giving me the opportunity to write this piece for them and thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this article, you can follow me on Twitter at @Reed_Wolfpack.

References and further reading:

- Private equity plays a starring role in 2020's SPAC boom | PitchBook

- PitchBook Analyst Note: The 2020 SPAC Frenzy

- US PE Breakdown | PitchBook

- Reports | PitchBook

FAQ | Q: Could you provide more related data and analytics? A: Sure, join Breakout Point and start benefitng from our services.

* Note: Unless otherwise stated, presented data and analytics is as of available on 2020-12-28, UTC 12:00.

The services and any information provided by Breakout Point or on the Breakout Point website shall not be, or construed to be any advice, guidance or recommendation to take, or not to take, any actions or decisions in relation to any investment, divestment or the purchase or sale of any assets, shares, participations or any securities of any kind. Any information obtained through Breakout Point and its services should never be used as a substitute for financial or other professional advice. Any decisions based on, or taken by use of, information obtained through Breakout Point and by its services are entirely at own risk.